A Developer's Guide To Docker - A Gentle Introduction

It works on my machine. We’ve all heard it. Most of us have said it. It’s been impossible to get around it… until now. Not only can adding Docker to your development environment solve that issue, but it can make it drop-dead simple to onboard new developers, keep a team working forward and allow everyone on the team use their desired tools!

Why Containers?

“Aren’t containers just lightweight Virtual Machines?”

That’s the question I get most often when I start talking to folks about containers. If it helps, you can think of them that way; but containers bring a lot more to the game than just a lightweight VM.

Before Containerization with Docker

It used to be, that if you wanted to host an application on your corporate network, it would take weeks. The operations team would have to make a request for the hardware, it would have to be approved, the finance department would have to make a purchase order, the ops team would have to order the hardware and when it got in, they’d have to put it in the server rack, get it on the network, install the operating system, and any other software needed to run your application. Of course, when ops people order servers, they don’t order the Intel Celeron processor and 512Mb of RAM; they get the 24, quad-core Xeon processor server with 15 bajillion gigabytes of RAM. This means that once your app is installed, the server runs at about 3% utilization. Not ideal from a CapEx and OpEx cost standpoint.

Enter the Virtual Machine

Virtual Machines helped with some of the utilization issues. You could use that monster server to host several VMs and get the utilization much closer to 80 or 90 percent. But you still had to install operating systems, software dependencies and make sure each gets patched with updates. This means logging into each virtual machine and updating and securing each. So if you have a farm of 20 VMs, that’s 20 times of logging in, loading patches, securing, etc. Some automation tools have made this process less labor-intensive, but it’s still not ideal. You’d also have to decide at design time how much resources to set aside for the virtual machine. Those resources are then lost by the host machine while the virtual machine is running.

Containers to the Rescue

Containers take the idea of the virtual machine one step farther. Instead of setting up a virtual machine and setting aside resources for it, you could let a container run like an application. It takes only as much resources as it needs to do it’s job. You can limit the amount of resources it can access, but when it’s doing nothing, it takes up almost no resources. When a virtual machine is doing nothing, it is still running a full-blown OS, and all the software that your application needs are still taking up resources.

Containers share the host operating system’s kernel. They run just like applications. They are given user space, but the underlying processes needed to run the application are owned by the host machine. This make them not only lightweight, but less resource intensive than VMs, because VMs need resources just to run the operating system and base processes. Having their own user space means that they are secured away from the host operating system, but they share kernel processes.

I am not a network or operations guy, I am just a developer. So it helps for me to think of containers as just applications, that think they’re full machines.

Assuming you have Docker installed, let’s dive in.

Some Technical Terminology

To get started, it’s important to get your head around two main terms: Images and Containers. Images are saved containers that you can then turn around and use to make other containers. If you’ve done any object-oriented development, you know that a class is a blueprint for creating an object. Images are like blueprints for creating containers.

Listing and Getting Images

To list the images you have downloaded to your host machine, run a simple command:

docker image list

You should see some headers, but nothing in the listing (unless you have pulled some container images before). I have a few images already on my machine.

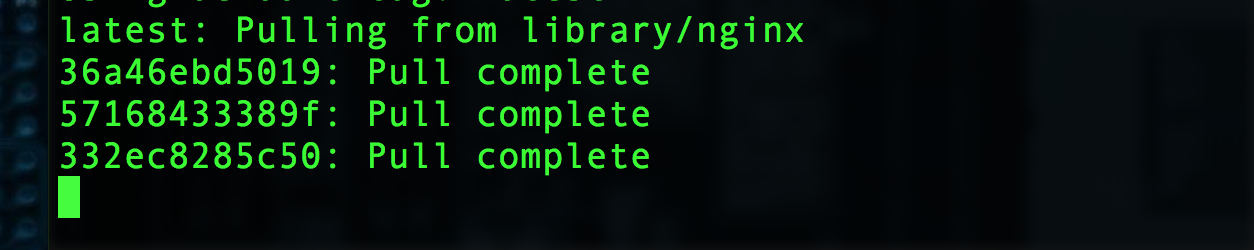

To pull the latest version of the NGINX image from Docker Hub, run the command:

docker pull nginx:latest

You can leave off the :latest and Docker will pull the image tagged with latest, but we’ll be explicit here. Just remember that :latest changes every time the owner of that image uploads a new version. So it’s not a good idea to use latest in production. Generally, the latest image will also have another tag (1.13.0 at the time of this article) that is much better to use for production. It will still be the same image, even if NGINX uploads a new version of the image tomorrow.

Running Containers

You can now run a container based on the nginx:latest image by running:

docker run -it nginx:latest /bin/bash

This tells Docker that we want to run a container based on the nginx:latest image, that we want it to be interactive (-i), that we want a pseudo tty shell (-t), and finally, we want the main command for this container to be /bin/bash. This runs the /bin/bash command at process ID 1 in the container. This means, when the bash shell in the container exits, the container will stop.

You should be dropped into a shell for the nginx container. We can open a new terminal while that one is running and see it from the host by typing:

docker container list

this should give is a listing like:

You can see the container’s ID is: 511b121137ac and at the command line inside the container, I am logged in as root@511b121137ac. You can also see the command is /bin/bash that is running at PID 1 in the container and the container name is determined_banach (it will be different for you). If you don’t specify a name for the container, Docker will make one from a list of adjectives and famous computer scientist last names (think hungry_babbage or slippery_bohr).

Now, if you type exit at the command line inside the container, we’ll be dropped back into the host machine’s command line. If we go to our other terminal (where we listed running containers) and re-run the docker container list command, we’ll see an empty list.

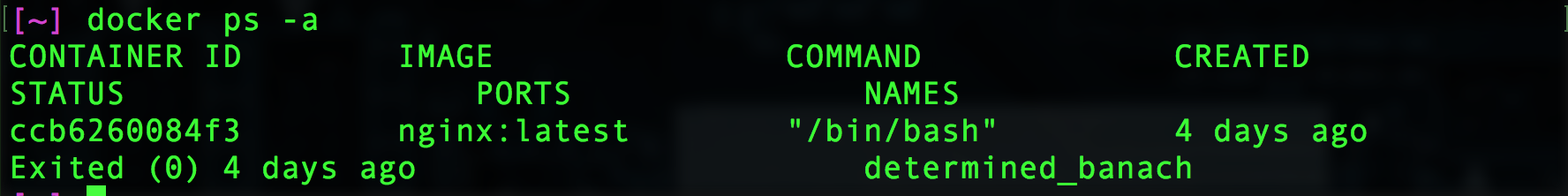

But what if you want to see all the containers whether they’re running or not? You can run the docker container list command with the -a switch (for all).

docker container list -a

As you can see the nginx-based container is now stopped and it exited with a code ‘0’, meaning it exited normally.

Cleaning Up Your Docker Environment

Just because the container isn’t running, doesn’t mean it’s gone. It’s still there in a stopped state. If you want to actually delete a container from your host machine you use the rm command like so:

docker rm determined_banach

You could also use the Container ID to remove a container, but you actually only have to give it as much of the ID as you need to make it unique in the list of containers. So if there are three containers on the host that all start with 41... you would just have to type the first three characters of the Container ID (416 for example) to remove it.

If you decide you don’t want to build any more containers from a particular image, you can remove it with the rmi command.

docker rmi nginx:latest

You don’t have to specify :latest for the image tag, Docker will assume you’re referring to :latest if you don’t specify, but it’s good practice to always use a tagged image. In a production scenario, it’s important to not use :latest, as the :latest image is updated whenever a new version of the image is pushed to the repository. So the image you get with the :latest tag today maybe very different from the one you got yesterday.

More Containers to Come!

Keep an eye out for future posts about Docker where we’ll look at creating images and containers from a Dockerfile and how to coordinate an environment of containers (API, database and UI) with Docker-Compose.

Okta Developer Blog Comment Policy

We welcome relevant and respectful comments. Off-topic comments may be removed.