Developer's Cheat Sheet for C# 9.0

Introduction to C# 9 (and a bit of C# 8, too)

Let’s start with a background on how C# 9 got here (implementation examples start in the next section).

The last few years in computer science, we’ve observed the rising popularity of the #FreeLunchOver concept. The idea is that CPU technology, based on electrical signals and Von Neumann architecture, has reached its intrinsic limits. As long as integrated circuits were slower than light, we knew we had work to do in improving the technology. But the time has come where, to go faster, we would need a faster medium and/or a different architecture. Scientists are all convinced that nothing can go faster than light. So, for the time being, engineers have explored the architecture path toward increasing speed. And they did exactly what the Industrial Revolution did to increase productivity - break the work into subunits, execute the subunits in parallel pipelines, and finally, assemble the resulting components. We began to see dual-core, quad-core processors… and we’ll probably soon see the day where exponential notation has to be used to express the number of cores in a CPU!

In the software industry this trend has produced significant effects. Programming paradigms that weren’t particularly relevant in sequential computing became more important, such as immutability, threading and asynchronous pipelines. Functional Programming (FP), previously relegated to academic and niche domains, gained more popularity in the commercial software arena. FP has characteristics that better adapt to parallel computing workflows than the Object Oriented Programming (OOP) that dominated programming language design for 20 years.

The first mainstream OOP language was C++, born as an OOP extension to the former procedural C. C++ has become an incredibly rich language without losing its fundamental trait, that is being an unmanaged language, which means it is close to the machine. With time, managed languages began to appear, where some aspects of the machine management, like memory allocation and especially deallocation and collection, have been promoted from “developer concern” to “machine concern”. As these features are not easy to implement in hardware, language creators invented the Virtual Machine (VM) concept. The VM is actually a piece of software itself that effectively makes available to the developer a different machine than the bare hardware. With time, VMs have become integral components of modern Operating Systems (OSs).

The most prominent example is probably Java, which conquered a vast share of the market with its free-to-use policy. There was a time where the big actors tried to ride the Java horse to their own advantage. But eventually Microsoft decided to create its own managed software framework, and .NET and C# were born.

When functional programming began to emerge, it became essential for these big actors to offer functional languages to the public for their own VM engines. They were constrained, though, as the languages needed to be compatible with their already grown OOP babies. So, after spending some time considering the already existing FP languages (Haskell and OCaml, to mention two of the most successful), they created new languages - Scala (Java VM) and F# (.NET VM). I am personally very passionate about functional programming, and an active F# advocate.

But progress never stops! Quantum computing seems to be the next hardware architecture frontier, which will of course invite new challenges for software engineers. These days, I am plunging into Microsoft Quantum Development Kit (QDK) and its associated language Q# - that’s another story for an upcoming post.

Back on earth, the OOP vs. FP gossip is very juicy. In the Microsoft realm, it seems to me that there’s more effort to make C# more functional, rather than F# more object oriented. There seems to be some strong resistance in the industry against FP, maybe because FP developed a reputation as more difficult and abstract. Which is not completely undeserved, though I’d say the reward makes the effort spent in learning it absolutely worth it.

Starting with version 7 and on with version 8 and 9, C# has seen several much welcome improvements, both in syntax and features. This post aims to collect some of those advancements, including real code examples. As a matter of fact, the title “Cheat Sheet” is a little… well, cheating. But I hope you’ll enjoy it anyhow.

Requirements to Develop with C# 9

The resources used for this post are:

- A computer with a .NET Core compatible Operating System (I used Windows 10)

- Your favorite .NET IDE (I used Visual Studio)

- .NET 5 SDK

The Visual Studio 2019 Sample Project

To follow the examples in this article, you need .NET 5 SDK. I’ll be using Visual Studio 2019 CE version 16.8.3. The code examples are in a solution in this GitHub repo.

Please create a new Solution with a .NET Core console Project. By default, the project uses .NET Core 3.1 as target framework, with C# 8 as the language version.

At the time of writing, all you need to enable C#9 in your project, is to select .NET 5 as target framework for your project, since .NET 5 used C#9 by default.

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<PropertyGroup>

<OutputType>Exe</OutputType>

<TargetFramework>net5.0</TargetFramework>

</PropertyGroup>

</Project>

With this, we are now ready to explore the new features C#8 and C#9 have to offer.

Immutability

Immutability is a property that symbols in a program can have. We are so used to the “variable” terminology, that there seems to be no distinction from a symbol we declare to identify some value, and the concept of variable. This is because OOP is centered around the concept of imperative assignment, where any symbols representing data can be mutated as we wish, hence perfectly matching the “variable” nomenclature.

FP, on the other hand, is centered on the opposite concept, that of immutability. The universally known “=” syntax has a different meaning: not assignment, but binding. So whatever is on the left is not variable anymore, but “invariable” if you like. (What a bad term!) That’s why I prefer to use the term “symbol,” in place of “variable”.

Sometimes we find opinions in the community that depict mutability as evil, advocating an almost religious superiority of FP over OOP. I don’t personally agree with this point of view. In my experience, having more tools makes things better, not worse. If nothing else, I can always decide not to use a tool I have, while I cannot use a tool I don’t have.

Also in my experience, OOP and FP are two powerful weapons in my arsenal. After the necessary familiarization period, now it’s natural to use both in designing new software, and I find they can get along pretty well (and this is one of the reasons why I like F#).

One myth I would like to dispel is that C# cannot define immutable types. It can, only it’s not quite made for this, so it requires some additional effort. The feature described in this section helps to avoid most of the boilerplate that was needed in previous versions.

Init-Only Properties (a.k.a. Immutable Reference Types)

The new keyword init can be used when declaring properties. Properties can be set only once at initialization.

using Xunit;

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.Immutability.InitOnlyProperties

{

class OktaOptionsClass_Mutable

{

public string OktaDomain { get; set; }

public int Retrials { get; set; }

}

class OktaOptionsClass_Immutable_Wrong

{

public string OktaDomain { get; }

public int Retrials { get; }

}

class OktaOptionsClass_Immutable_Constructor

{

public string OktaDomain { get; }

public int Retrials { get; }

public OktaOptionsClass_Immutable_Constructor(string oktaDomain, int retrials)

{

OktaDomain = oktaDomain;

Retrials = retrials;

}

}

class OktaOptionsClass_Immutable_Ok_Init

{

public string OktaDomain { get; init; }

public int Retrials { get; init; }

}

public class Tests

{

[Fact]

public void Test()

{

var options_mutable =

new OktaOptionsClass_Mutable {

OktaDomain =

@"https://dev-509249.okta.com", Retrials = 3 };

options_mutable.Retrials = 9458257; //properties can be set at any time

//Compiler error, cannot set properties (at all)

//var options_immutable_wrong =

// new OktaOptionsClass_Immutable_Wrong {

// OktaDomain = @"https://dev-509249.okta.com",

// Retrials = 3 };

//Ok, use constructor

var options_immutable_ok = new OktaOptionsClass_Immutable_Constructor(@"https://dev-509249.okta.com", 3);

//options_immutable_ok.Retrials = 9458257; //design time error: properties are readonly

//Ok, new init-only properties

var options_immutable_ok_init =

new OktaOptionsClass_Immutable_Ok_Init {

OktaDomain = @"https://dev-509249.okta.com",

Retrials = 3 };

//options_immutable_ok_init.Retrials = 9458257; //design time error: properties are readonly

}

}

}

There are 4 different versions of a class with different degrees of immutability:

- OktaOptionsClass_Mutable; mutable, properties can be changed at any time

- OktaOptionsClass_Immutable_Wrong; immutable, but also useless as there is no way to set the properties

- OktaOptionsClass_Immutable_Constructor; old way immutable, requiring to write a “dumb” constructor

- OktaOptionsClass_Immutable_Ok_Init; new way immutable, less boilerplate (you don’t need to write the “dumb” constructor)

Records

A new type of declaration named record makes it easier to work with complex types. For example:

- Record variables are object references like class types

- Equality is by value, like struct types

- Immutability features (copy constructor/cloning, deconstructor, deep equality logic) are created for us by the compiler

using Xunit;

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.Immutability.Records

{

class OktaOptionsClass

{

public string OktaDomain { get; set; }

public int Retrials { get; set; }

public OktaOptionsClass(string oktaDomain, int retrials)

{

OktaDomain = oktaDomain;

Retrials = retrials;

}

}

struct OktaOptionsStruct

{

public string OktaDomain { get; set; }

public int Retrials { get; set; }

public OktaOptionsStruct(string oktaDomain, int retrials)

{

OktaDomain = oktaDomain;

Retrials = retrials;

}

}

record OktaOptionsNominalRecord

{

public string OktaDomain { get; set; }

public int Retrials { get; set; }

}

public class Tests

{

[Fact]

public void Test()

{

//class semantic: 2 objects are created and 3 references

//The variables option_class_* represent the references, not the content

var options_class_1 = new OktaOptionsClass(@"https://dev-509249.okta.com", 5);

var options_class_2 = new OktaOptionsClass(@"https://dev-509249.okta.com", 5);

//Reference copy

var options_class_3 = options_class_1;

//struct semantic: 3 objects are created and no references

//The variables option_struct_* represent content

var options_struct_1 = new OktaOptionsStruct(@"https://dev-509249.okta.com", 5);

var options_struct_2 = new OktaOptionsStruct(@"https://dev-509249.okta.com", 5);

//value copy

var options_struct_3 = options_struct_1;

//record semantic: as class semantic when instanciating

var options_record_1 = new OktaOptionsNominalRecord { OktaDomain = @"https://dev-509249.okta.com", Retrials = 5 };

var options_record_2 = new OktaOptionsNominalRecord { OktaDomain = @"https://dev-509249.okta.com", Retrials = 5 };

//Reference copy

var options_record_3 = options_record_1;

//class semantic: despite pointing to identical contents, only variables _1 and _3 are compared equal

//this is because the compiler generates reference, not content, comparison code

Assert.NotEqual(options_class_1, options_class_2);

Assert.NotEqual(options_class_2, options_class_3);

Assert.Equal(options_class_1, options_class_3);

options_class_1.Retrials = 7;

Assert.Equal(7, options_class_3.Retrials);

//class semantic: only content has been changed, not references, so comparisons are unchanged

Assert.NotEqual(options_class_1, options_class_2);

Assert.NotEqual(options_class_2, options_class_3);

Assert.Equal(options_class_1, options_class_3);

//struct semantic: compiler generates value comparison (no reference is created for structs)

Assert.Equal(options_struct_1, options_struct_2);

Assert.Equal(options_struct_2, options_struct_3);

Assert.Equal(options_struct_1, options_struct_3);

options_struct_1.Retrials = 7;

//struct semantic: the variables option_struct_* represent the content

//so the change in value is reflected in variable comparison

Assert.NotEqual(options_struct_1, options_struct_2);

Assert.Equal(options_struct_2, options_struct_3);

Assert.NotEqual(options_struct_1, options_struct_3);

//record semantic: even though the variables represent references, the compiler generates

//value comparison code. The behavior is like struct

Assert.Equal(options_record_1, options_record_2);

Assert.Equal(options_record_2, options_record_3);

Assert.Equal(options_record_1, options_record_3);

options_record_1.Retrials = 7;

//record semantic: after a content change, comparisons behave as class, not struct (variables are references)

Assert.NotEqual(options_record_1, options_record_2);

Assert.NotEqual(options_record_2, options_record_3);

Assert.Equal(options_record_1, options_record_3);

}

}

}

In this code sample, I am declaring three different data types with the same content, but different language implementation. Please refer to the comments for more detailed information.

Notice however that in this paragraph I am using record with enforced mutability (where properties have set accessors), in order to compare them to the traditional mutable constructs offered by the language. Records, though, are designed to make it particularly easy to work with immutable data.

Positional Records

Records offer a particularly lean notation to create immutable objects

using System;

using Xunit;

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.Immutability.Positional

{

class OktaOptionsClass

{

public string OktaDomain { get; init; }

public int Retrials { get; init; }

public OktaOptionsClass(string oktaDomain, int retrials)

{

OktaDomain = oktaDomain;

Retrials = retrials;

}

public override bool Equals(object obj)

{

var other = (OktaOptionsClass)obj;

return OktaDomain.Equals(other.OktaDomain) && Retrials.Equals(other.Retrials);

}

//Declaring a Deconstruct method simplifies retrieving properties

//(automatically generated by the compiler for records)

public void Deconstruct(out string domain, out int retrials)

=> (domain, retrials) = (OktaDomain, Retrials);

public override int GetHashCode()

{

return OktaDomain.GetHashCode() ^ Retrials.GetHashCode();

}

OktaOptionsClass Clone()

{

return new OktaOptionsClass(OktaDomain, Retrials);

}

public OktaOptionsClass(OktaOptionsClass oktaOptions) => oktaOptions.Clone();

}

public record OktaOptionsPositionalRecord(string OktaDomain, int Retrials);

//Records can be derived as classes

public record OktaOptionsPositionalRecordDerived(string OktaDomain, int Retrials, DateTime ExpirationDate)

: OktaOptionsPositionalRecord(OktaDomain, Retrials)

{

//Compiler generates copy constructor automatically for records

public OktaOptionsPositionalRecordDerived Copy()

=> new OktaOptionsPositionalRecordDerived(this);

}

public class Tests

{

[Fact]

public void Test()

{

//Compiler generates automatically a initializing constructor for records

var options_class_1 = new OktaOptionsClass(@"https://dev-509249.okta.com", 5);

var options_record_1 = new OktaOptionsPositionalRecord(@"https://dev-509249.okta.com", 5);

//Compiler generates automatically init-only property accessors for records

var domain = options_record_1.OktaDomain;

var retrials = options_record_1.Retrials;

//options_record_1.Retrials = 7; //Compiler error, properties are init-only

//Traditional object deconstruction

var (domain_class, retrials_class) = (options_class_1.OktaDomain, options_class_1.Retrials);

//New object deconstruction based on custom Deconstructor method

var (_domain_class, _retrials_class) = options_class_1;

//Compiler generates automatically deconstructor for records

var (domain_record, retrials_record) = options_record_1;

var options_record_derived_1 =

new OktaOptionsPositionalRecordDerived(@"https://dev-509249.okta.com", 5, DateTime.Now);

//Copying through method (explicit use of the automatically generated copy constructor)

var options_record_derived_2 = options_record_derived_1.Copy();

Assert.Equal(options_record_derived_1, options_record_derived_2);

//Copying through with expression (implicit use of the automatically generated copy constructor)

var options_record_derived_3 = options_record_derived_1 with { };

Assert.Equal(options_record_derived_1, options_record_derived_3);

//With expression can generate a modified copy

var options_record_derived_4 = options_record_derived_1 with { OktaDomain = "OktaUrl2" };

var (_, retrials_1, expiration_1) = options_record_derived_1;

var (_, retrials_4, expiration_4) = options_record_derived_4;

Assert.Equal((retrials_1, expiration_1), (retrials_4, expiration_4));

//With expression modified fields can refer to original record's fields

var options_record_derived_5 =

options_record_derived_1 with { ExpirationDate = options_record_derived_1.ExpirationDate.AddDays(1.0) };

var (domain_1, _, _) = options_record_derived_1;

var (domain_5, retrials_5, _) = options_record_derived_5;

Assert.Equal((domain_1, retrials_1), (domain_5, retrials_5));

}

}

}

Note: OktaOptionsPositionalRecord behaves as OktaOptionsClass. In other words, C# now offers syntactic sugar to add immutability boilerplate to class based types automatically. You simply have to declare your type as record instead of class. A Deconstruct method can be defined in a class type. This is also a new feature created to implement records, but can be used in non-record types.

Static Local Functions

One of the principles of functional programming, along with immutability, is “No side effects.” This means a function should produce results only as a return value, and data needs to be passed in as a parameter in order to to produce it. This is what static local functions are all about.

We can ensure that local functions, lambdas, and anonymous methods are side-effect free. The compiler will refuse to compile them if they access data outside their context.

using System;

using Xunit;

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.StaticLocalFunctions.LocalClosureCapture

{

public class Tests

{

[Fact]

public void Local_function()

{

int x = 1;

int AddWithCapture(int a, int b)

{

x = 5;

return a + b;

}

//static: trying to use x will cause a compiler error

static int AddWithoutCapture(int a, int b)

{

//x = 5; // Error

return a + b;

}

//static local functions CANNOT change external in-scope locals (x here)

Assert.Equal(2, AddWithoutCapture(x, 1));

//No side effects

Assert.Equal(2, x + 1);

//Non static local functions CAN change external in-scope locals (x here)

Assert.Equal(2, AddWithCapture(x, 1));

//Here the side effect is to change the result of a test with the same inputs

Assert.NotEqual(2, x + 1);

}

[Fact]

public void Lambda()

{

int x = 1;

Func<int, int, int> addWithCapture = (a, b) => { x = 5; return a + b; };

Func<int, int, int> addWithoutCapture = static (a, b) => { /*x = 9; //error */ return a + b; };

//static lambdas CANNOT change external in-scope locals (x here)

Assert.Equal(2, addWithoutCapture(x, 1));

//No side effects

Assert.Equal(2, x + 1);

//Non static lambdas CAN change external in-scope locals (x here)

Assert.Equal(2, addWithCapture(x, 1));

//Here the side effect is to change the result of a test with the same inputs

Assert.NotEqual(2, x + 1);

//Same with lambdas

}

}

}

Default Interface Methods

Default interface methods are a new feature, and are not strictly related to the FP enrichment, but they’re a very nice to have, especially for Library authors.

Non Breaking Interface Augmentation

Library authors have the possibility to add interface members without breaking applications.

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.DefaultInterfaceMethods.NonBreakingInterfaceAugmentation

{

//Library Version 1

namespace Version1

{

namespace Library

{

interface ILibraryInterface

{

int Increment(int i);

}

}

namespace Application

{

using Library;

class UserClass : ILibraryInterface

{

public int Increment(int i) => i + 1;

}

}

}

//Library Version 2: Add Decrement method to interface

//This change is breaking, because it forces the user to modify her code,

//and add an implementation for the added method

namespace Version2_Ideal

{

namespace Library

{

interface ILibraryInterface

{

int Increment(int i);

int Decrement(int i);

}

}

namespace Application

{

using Library;

//Compiler error: User Class doesn't implement ILibraryInterface

//class UserClass : ILibraryInterface

//{

// public int Increment(int i) => i + 1;

//}

class UserClass : ILibraryInterface

{

public int Increment(int i) => i + 1;

//User is force to add Decrement implementation

public int Decrement(int i) => i - 1;

}

}

}

//Library Version 2 with additional interface

//This change is not breaking, but it imposes the creation of new interface

//with consequent naming pollution and messy architecture

namespace Version2_Additional_Interface

{

namespace Library

{

interface ILibraryInterface

{

int Increment(int i);

}

interface ILibraryInterface2 : ILibraryInterface

{

int Decrement(int i);

}

}

namespace Application

{

using Library;

class UserClass : ILibraryInterface

{

public int Increment(int i) => i + 1;

}

}

namespace Application_Version2

{

using Library;

//To use the new library features, UserClass needs to implement 2 interfaces

class UserClass : ILibraryInterface, ILibraryInterface2

{

public int Increment(int i) => i + 1;

public int Decrement(int i) => i - 1;

}

}

}

//Library Version 2 with default implementation (C#8)

//This change is not breaking, and avoids the issues above

namespace Version2_Default_Implementation

{

namespace Library

{

interface ILibraryInterface

{

int Increment(int i);

int Decrement(int i) => i - 1;

}

}

namespace Application

{

using Library;

class UserClass : ILibraryInterface

{

public int Increment(int i) => i + 1;

}

}

}

}

Note: The application code can always override the default interface implementation for Decrement when needed.

Pattern Matching

Pattern matching is a typical FP concept. As is often the case, explaining with words is more difficult than showing how it works. Though we could say that pattern matching belongs in that category of those improvements that allow us to write code that performs traditional things in a more succinct and expressive syntax.

Switch Expression

The new switch expression and the added relational and logical operators give us a more powerful and expressive way to carry out decision-making workflows.

using System.Linq;

using Xunit;

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.PatternMatching.SwitchExpression

{

static class ScoreEvaluator

{

static internal string SwitchStatement(int score)

{

var ret = string.Empty;

switch(score)

{

case 0:

ret = "Unclassified";

break;

case 1:

case 2:

case 3:

ret = "Bad";

break;

case 4:

case 5:

ret = "Ordinary";

break;

case 6:

case 7:

ret = "Good";

break;

case 8:

case 9:

ret = "Excellent";

break;

case 10:

ret = "Outstanding";

break;

default:

ret = "Invalid Score";

break;

}

return ret;

}

static internal string SwitchExpression(int score) => score switch

{

0 => "Unclassified",

> 0 and <= 3 => "Bad",

4 or 5 => "Ordinary",

>= 6 and <= 7 => "Good",

8 or 9 => "Excellent",

10 => "Outstanding",

_ => "Invalid Score"

};

}

public class Tests

{

[Fact]

public void Test()

{

Assert.All(

Enumerable.Range(-1, 12),

i => Assert.Equal(ScoreEvaluator.SwitchExpression(i), ScoreEvaluator.SwitchStatement(i)));

}

}

}

The new pattern-matching coding in SwitchExpression is evidently more terse and expressive, stripping out a great deal of boilerplate needed in the traditional SwitchStatement implementation.

Type Check Pattern

We find similar welcome improvements when the decision-making workflow involves type checking.

using System;

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.PatternMatching.TypeCheckPattern

{

class Cube

{

public double Side { get; }

}

class Sphere

{

public double Radius { get; }

}

class Cone

{

public double Radius { get; }

public double Height { get; }

}

class Volume

{

static double Traditional(object solid)

{

if (solid.GetType().Equals(typeof(Cube)))

{

var cube = solid as Cube;

if (cube.Side >= 0.0)

return Math.Pow(cube.Side, 3);

}

else if (solid.GetType().Equals(typeof(Sphere)))

{

var sphere = solid as Sphere;

return 4.0 / 3.0 * Math.PI * Math.Pow(sphere.Radius, 3);

}

else if (solid.GetType().Equals(typeof(Cone)))

{

var cone = solid as Cone;

if (cone.Radius >= 0.0 && cone.Height >= 0)

return Math.PI * Math.Pow(cone.Radius, 2) * cone.Height / 3.0;

}

return double.NaN;

}

static double IsStatement(object solid)

{

if (solid is Cube cube && cube.Side >= 0.0)

return Math.Pow(cube.Side, 3);

else if (solid is Sphere sphere && sphere.Radius >= 0.0)

return 4.0 / 3.0 * Math.PI * Math.Pow(sphere.Radius, 3);

else if (solid is Cone cone && cone.Radius >= 0.0 && cone.Height >= 0)

return Math.PI * Math.Pow(cone.Radius, 2) * cone.Height / 3.0;

return double.NaN;

}

static double SwitchStatement(object solid)

{

switch(solid)

{

case Cube cube when cube.Side > 0.0:

return Math.Pow(cube.Side, 3);

case Sphere sphere when sphere.Radius >= 0.0:

return 4.0 / 3.0 * Math.PI * Math.Pow(sphere.Radius, 3);

case Cone cone when cone.Radius >= 0.0 && cone.Height >= 0.0 :

return Math.PI * Math.Pow(cone.Radius, 2) * cone.Height / 3.0;

default: return double.NaN;

}

}

static double SwitchExpression(object solid) => solid switch

{

Cube cube when cube.Side >= 0.0 => Math.Pow(cube.Side, 3),

Sphere sphere when sphere.Radius >= 0.0 => 4.0 / 3.0 * Math.PI * Math.Pow(sphere.Radius, 3),

Cone cone when cone.Radius >= 0.0 && cone.Height >= 0.0 => Math.PI * Math.Pow(cone.Radius, 2) * cone.Height / 3.0,

_ => double.NaN,

};

static double CascadeSwitchExpression(object solid) => solid switch

{

Cube cube =>

cube.Side switch

{

>= 0.0 => Math.Pow(cube.Side, 3),

_ => throw new ArgumentException("..."),

},

Sphere sphere =>

sphere.Radius switch

{

>= 0.0 => 4.0 / 3.0 * Math.PI * Math.Pow(sphere.Radius, 3),

_ => throw new ArgumentException("..."),

},

Cone cone =>

(cone.Radius, cone.Height) switch

{

(>= 0.0, >= 0.0) => Math.PI * Math.Pow(cone.Radius, 2) * cone.Height / 3.0,

_ => throw new ArgumentException("..."),

},

_ => double.NaN,

};

}

}

In the above, observe how:

- Readability improves significantly from the “traditional” way, compared to the new expressive pattern matching flavors

- We need to write much less when using pattern matching, which both saves time and reduces errors. (After all, there is no code more correct that the one we don’t write!)

The last example CascadeSwitchExpression is not equivalent to the examples before that, as it also raises validation exceptions. Rather, it’s an example showing how to nest switch expressions.

Property Pattern

Last but not least, checking properties values in decision workflows is a great improvement.

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.PatternMatching.PropertyPattern

{

class PropertyPattern

{

enum Companies { C1, C2, C3 };

enum Zones { Z1, Z2, Z3 };

class ZonalClient

{

public Companies Company { get; }

public Zones Zone { get; }

public int Purchases { get; }

}

class DiscountApplier

{

int Traditional(ZonalClient client)

{

if (client.Purchases >= 500)

return 50;

else if (client.Purchases >= 200 && client.Purchases < 500)

return 30;

else if (client.Company == Companies.C1

&& (client.Zone == Zones.Z1 || client.Zone == Zones.Z3)

&& client.Purchases >= 150)

return 25;

else if (client.Purchases >= 150

|| (client.Company == Companies.C2 && client.Purchases >= 100))

return 20;

else if ((client.Zone == Zones.Z2 && client.Purchases >= 50)

|| ((client.Company == Companies.C2 || client.Company == Companies.C3)

&& client.Zone == Zones.Z3))

return 15;

else if (client.Purchases >= 25)

return 5;

else return 0;

}

int PropertyPattern(ZonalClient client) => client switch

{

{ Purchases: >= 500 } => 50,

{ Purchases: >= 200 and < 500 } => 30,

{ Company: Companies.C1, Zone: Zones.Z1 or Zones.Z3, Purchases: >= 150 } => 25,

{ Purchases: >= 150 } or { Company: Companies.C2, Purchases: >= 100 } => 20,

{ Zone: Zones.Z2, Purchases: >= 50 } or { Company: Companies.C2 or Companies.C3, Zone: Zones.Z3 } => 15,

{ Purchases: >= 25 } => 5,

_ => 0

};

}

}

}

Understanding what the code does becomes much much easier, don’t you agree?

Compactness

Many of the new features you saw go towards a language that is not only more powerful, but that also removes boilerplate and adds more expressiveness. This chapter shows more of them.

Indices and Ranges

Slicing an indexed collection of items (array) can be done using the new back-indexing (^) and range (..) operators

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.IndicesAndRanges.Slicing

{

using System;

using System.Linq;

using Xunit;

using static Collection;

internal class Collection

{

static int milliseconds = DateTime.Now.Millisecond;

public static Random Rand = new Random(milliseconds);

public static int[] a = Enumerable.Range(0, Rand.Next(100, 1000)).Select(i => Rand.Next()).ToArray();

}

public class Tests

{

[Fact]

public void Past_end()

{

Assert.Throws<IndexOutOfRangeException>(() => a[a.Length]);

Assert.Throws<IndexOutOfRangeException>(() => a[^0]);

}

[Fact]

public void First_element()

{

Assert.Equal(a[0], a[^a.Length]);

}

[Fact]

public void Last_element()

{

Assert.Equal(a[a.Length - 1], a[^1]);

}

[Fact]

public void First_15()

{

Assert.Equal(a.Take(15), a[..15]);

}

[Fact]

public void Last_27()

{

Assert.Equal(a.Skip(a.Length - 27).Take(27), a[^27..]);

}

[Fact]

public void From_11_to_43()

{

Assert.Equal(a.Skip(11).Take(32), a[11..43]);

}

[Fact]

public void From_37_to_6_back()

{

Assert.Equal(a.Skip(a.Length - 37).Take(37 - 6), a[^37..^6]);

}

[Fact]

public void Starting_slice()

{

int to = Rand.Next(a.Length);

Assert.Equal(a.Take(to), a[..to]);

}

[Fact]

public void Ending_slice()

{

int from = Rand.Next(a.Length);

Assert.Equal(a.Skip(from), a[from..]);

}

[Fact]

public void Any_slice()

{

int from = Rand.Next(a.Length / Rand.Next(2, 4));

int size = Rand.Next(a.Length / Rand.Next(3, 5));

int to = from + size;

Assert.Equal(a.Skip(from).Take(size), a[from..to]);

}

[Fact]

public void Any_slice_back()

{

int from = Rand.Next(a.Length / Rand.Next(2, 4));

int size = Rand.Next(a.Length / Rand.Next(3, 5));

int to = from + size;

Assert.Equal(a.Skip(a.Length - to).Take(size), a[^to..^from]);

}

}

}

Working with the end of an array has become as easy as working with the front.

Null Coalescing

Two new operators make it easier checking on nulls:

- ??: Null coalescing operator. In place of the old a != null ? a : b or a == null ? b : a, you can now simply write a ?? b

- ??=: Null coalescing assignment operator. It allows write a ??= b to assign b to a only if a is null, like in the old a = a != null ? a : b

using System.Collections.Generic;

using Xunit;

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.NullCoalescing.Operators

{

public class Tests

{

[Fact]

public void Null_coalescing_operator()

{

(object a, object b, object c, object d) = (new object(), null, new object(), null);

Assert.Equal(a, a != null ? a : c); //old

Assert.Equal(a, a ?? c); //new

Assert.Equal(c, b != null ? b : c); //old

Assert.Equal(c, b ?? c); //new

Assert.Equal(c, d != null ? d : b != null ? b : c != null ? c : a); //old

Assert.Equal(c, d ?? b ?? c ?? a); //new

object[] array = { a, b, c, d };

for(int i = 2; i < 4; i++)

{

foreach (var combination in Combinatory.Combinations(array, i))

{

AssertCombination(combination);

}

}

void AssertCombination(object[] combination)

{

switch(combination)

{

case object[] array when array.Length == 2:

var (a, b) = (array[0], array[1]);

Assert.Equal(a != null ? a : b, a ?? b);

break;

case object[] array when array.Length == 3:

var (c, d, e) = (array[0], array[1], array[2]);

Assert.Equal(c != null ? c : d != null ? d : e, c ?? d ?? e);

break;

case object[] array when array.Length == 4:

var (f, g, h, i) = (array[0], array[1], array[2], array[3]);

Assert.Equal(f != null ? f : g != null ? g : h != null ? h : i, g ?? f ?? h ?? i);

break;

}

}

}

[Fact]

public void Null_coalescing_assignment()

{

(object a1, object b1, object c1) = (new object(), null, new object());

(object a2, object b2, object c2) = (new object(), null, new object());

Assert.NotNull(a1); Assert.NotNull(a2);

a1 = a1 != null ? a1 : c1; //old

a2 ??= c2; //new

Assert.NotNull(a1); Assert.NotNull(a2);

Assert.NotEqual(a1, c1); Assert.NotEqual(a2, c2);

Assert.Null(b1); Assert.Null(b2);

b1 = b1 != null ? b1 : c1; //old

b2 ??= c2; //new

Assert.NotNull(b1); Assert.NotNull(b2);

Assert.Equal(b1, c1); Assert.Equal(b2, c2);

}

}

static class Combinatory

{

public static IEnumerable<T[]> Combinations<T>(T[] array, int size)

{

T[] result = new T[size];

foreach (int[] j in Combinations(size, array.Length))

{

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++)

{

result[i] = array[j[i]];

}

yield return result;

}

}

private static IEnumerable<int[]> Combinations(int size, int length)

{

int[] result = new int[size];

Stack<int> stack = new Stack<int>(size);

stack.Push(0);

while (stack.Count > 0)

{

int index = stack.Count - 1;

int value = stack.Pop();

while (value < length)

{

result[index++] = value++;

stack.Push(value);

if (index != size) continue;

yield return (int[])result.Clone();

break;

}

}

}

}

}

Null coalescing operators are really helpful with the “null billion dollar mistake”. Usually in C#, checking for nulls populates a great deal of our source files. The new operators do not get rid of null, but they make it much less annoying to deal with.

Target Type Inference

Target type inference moves us further towards writing less boilerplate. The compiler’s type inference power has been increased so that we don’t need to specify the type in a new statement if the new instance is meant to be referenced by a typed symbol. In the following example you can observe three different cases

using Xunit;

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.FitAndFinish.TargetTypeInference

{

record MyType(int Value = 0);

public class Tests

{

[Fact]

public void Create_new_instance()

{

var a = new MyType(12); //old way

MyType b = new(12); //new way

Assert.Equal(b, a);

}

[Fact]

public void Function_call()

{

int Double(MyType myVar) => myVar.Value * 2;

var a = Double(new MyType(7)); //old way

var b = Double(new (7)); //new way

Assert.Equal(b, a);

}

[Fact]

public void Property_init()

{

var a = new MyType() { Value = 61 }; //old way

MyType b = new() { Value = 61 }; // new way

Assert.Equal(b, a);

}

}

}

- Type indication replaces the var declaration, so the right side of the assignment operator doesn’t need to repeat the type

- The type of the newly instantiated object is already clear by the called function (Double) declaration

- Similar to 1, but with property initialization

In other words, when the compiler finds a new statement without a type name, it looks around if the object to be instantiated has a target symbol (or a function parameter) where the type is specified. Hence the name “target type inference.”

Type Extensibility

These additions belong to the group of features that empower the use of third-party libraries. (We already saw one above, the default interface methods). In that case, the feature allows library users to supply new versions of their product by adding members to existing interfaces without forcing the user to refactor the application code. The amenities discussed in this section all facilitate users of third-party libraries to extend the library with more powerful constructs.

Covariant Returns

The very native extension pattern in OOP is inheritance. Members can be declared virtual when defining a type, allowing the user to override them in derived types. Traditionally, though, method overrides need to maintain the same signature of the base’s. Covariant returns means that we can now define overridden methods with different return types than the base ones, provided that the override return type is derived from the base return type. Returning derived types from overrides was possible even before, but it required the call site to perform a cast or a type check. Well, not anymore.

using System;

using Xunit;

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.FitAndFinish.CovariantReturns

{

namespace OldWay

{

class Thing

{

public string Name { get; init; }

}

class Place : Thing

{

public string Area { get; init; }

}

class Country : Place

{

public string Capital { get; init; }

}

class Event

{

public virtual Thing Get() => new Thing { Name = "Big Bang" };

}

class Trip : Event

{

public override Thing Get() => new Place { Name = "Cruise", Area = "Mediterrnanean Sea" };

}

class Holiday : Trip

{

public override Thing Get() => new Country { Name = "Australia", Area = "Oceania", Capital = "Canberra" };

}

public class Tests

{

[Fact]

public void Test()

{

var (@event, trip, holiday) = (new Event(), new Trip(), new Holiday());

var thing = @event.Get();

var thingName = thing.Name;

var place = trip.Get();

var placeName = place.Name;

//var placeArea = place.Area; //compiler error: Area is not Thing class' member

var place1 = (Place)trip.Get(); //cast required

var placeArea = place1.Area; //ok

var country = holiday.Get();

var countryName = country.Name;

//var countryArea = country.Area; //compiler error: Area is not Thing class' member

//var countryCapital = country.Capital; //compiler error: Capital is not Thing class' member

var country1 = (Place)holiday.Get(); //cast to Place

var countryArea = country1.Area; //ok

//var countryCapital = country1.Capital; //compiler error: Capital is not Place class' member

var country2 = (Country)holiday.Get(); //cast to Country

var countryCapital = country2.Capital; //ok

Assert.Throws<InvalidCastException>(() => (Place)@event.Get()); //Runtime error

Assert.Throws<InvalidCastException>(() => (Country)@event.Get()); //Runtime error

Assert.Throws<InvalidCastException>(() => (Country)trip.Get()); //Runtime error

}

}

}

namespace NewWay

{

class Thing

{

public string Name { get; init; }

}

class Place : Thing

{

public string Area { get; init; }

}

class Country : Place

{

public string Capital { get; init; }

}

class Event

{

public virtual Thing Get() => new Thing { Name = "Big Bang" };

}

class Trip : Event

{

public override Place Get() => new Place { Name = "Cruise", Area = "Mediterrnanean Sea" };

}

class Holiday : Trip

{

public override Country Get() => new Country { Name = "Australia", Area = "Oceania", Capital = "Canberra" };

}

public class Tests

{

[Fact]

public void Test()

{

var (@event, trip, holiday) = (new Event(), new Trip(), new Holiday());

var thing = @event.Get();

var thingName = thing.Name;

var place = trip.Get();

var placeName = place.Name;

var placeArea = place.Area; //ok, place has already the correct type, no cast required

var country = holiday.Get();

var countryName = country.Name;

var countryArea = country.Area; //ok, country has already the correct type, no cast required

var countryCapital = country.Capital; //ok, country has already the correct type, no cast required

//As cast is not required, the possibility of runtime errors due to wrong cast is eliminated

}

}

}

}

In the above example, the namespace OldWay shows how to return derived types from overrides before this feature was added, whilst NewWay shows how with the new feature we can avoid casts, and also declaratively assert clearly that we are returning a derived type.

Enumerability By Extension

Another concept borrowed from FP is “laziness”. Laziness allows us to write more modular code, that is to say, implement a better separation of concerns. We can write code that produces a result, without executing it immediately, but deferring the execution to a later time when the result is effectively accessed. A textbook scenario is a database query. Often our programs contain iterative or event-based workflows - where we check some conditions and based on the check we run one of multiple different queries. Without laziness, we would need to put the query code inline with the condition-check, or alternatively pre-calculate all the possible results in the cached collection to be used in the iteration. With laziness, we get both. We can write the query code in one place and declare it as lazy. Somewhere else, in our codebase, we can then write the iteration accessing the data as if it were cached - when in reality the compile has hooked a call to our lazy code.

Laziness in constructing collections is not new in C# — the IEnumerable and IEnumerable<T> generic interfaces were available well before version 8 of the language.

What is new, though, is the possibility to add this feature to existing types via type extensions. Previously, Enumerable types needed to implement IEnumerable or IEnumerable<T>. Today, this is not strictly necessary. What is required is to provide a public GetEnumerator method returning an instance of a type that defines two public members: a Current property and a bool MoveNext parameterless method.

And this GetEnumerator method can be an extension method, so we can add enumerability to a library type (where previously the only way was to add an IEnumerable implementation which required access to the source code and recompilation of the library).

using System;

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using Xunit;

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.FitAndFinish.EnumerableByExtension

{

class EnumerableTour : IEnumerable

{

public string Day1 => "New York";

public string Day2 => "Boston";

public string Day3 => "Washington DC";

public IEnumerator GetEnumerator()

{

return new Enumerator(this);

}

class Enumerator : IEnumerator

{

EnumerableTour _tour;

public Enumerator(EnumerableTour tour)

{

_tour = tour;

}

int _index;

public object Current => _index switch

{

0 => _tour.Day1,

1 => _tour.Day2,

2 => _tour.Day3,

_ => "Please buy a new Tour"

};

public bool MoveNext() => (_index = Math.Max(_index++, 3)) < 3;

public void Reset() => _index = 0;

}

}

public class NonEnumerableTour

{

public string Day1 => "Chicago";

public string Day2 => "Las Vegas";

public string Day3 => "Miami";

}

static public class Extensions

{

public class MyEnumerator

{

NonEnumerableTour _tour;

int _index = 0;

public MyEnumerator(NonEnumerableTour tour)

{

_tour = tour;

}

public string Current => _index switch

{

0 => _tour.Day1,

1 => _tour.Day2,

2 => _tour.Day3,

_ => "Please buy a new Tour"

};

public bool MoveNext() => (_index = Math.Max(_index++, 3)) < 3;

}

public static MyEnumerator GetEnumerator(this NonEnumerableTour tour) => new MyEnumerator(tour);

}

public class Tests

{

[Fact]

public void This_tour_is_for_me()

{

var lovedCities = new HashSet<string>( new [] { "New York", "Chicago", "Washington DC", "Las Vegas", "Los Angeles", "Boston", "Miami" });

foreach (var city in new EnumerableTour()) Assert.Contains(city, lovedCities);

foreach (var city in new NonEnumerableTour()) Assert.Contains(city, lovedCities);

}

}

}

In the previous code example, EnumerableTour implements IEnumerable but NonEnumerableTour doesn’t. However, in the test, we can see that both types allow you to enumerate their cities through foreach. What makes this possible is the Extension class code, where GetEnumerator is defined as an extension method for NonEnumerableTour. If NonEnumerableTour was in a NuGet library, this extensibility wouldn’t have been possible previously. If you wanted it, you had to change the source code and transform NonEnumerableTour into EnumerableTour, and recompile the NuGet package (or create a derived type implementing IEnumerable).

Asynchronous Streams

Asynchronous streams are a powerful feature aimed to improve resource usage, especially in scenarios characterized by a particular type of data source, known under the name of streams. With the ever-increasing pervasiveness of networking and distribution, the new generation of applications will need to deal with increasingly sparse data.

Once upon a time, computers got data through perforated cards and spit out results as line-printed-paper trails. Then we passed to magnetic supports and phosphorus screens… Step by step, we came to these days where almost everything external to the unit we are programming is identified by an internet URI (Uniform Resource Identifier). It doesn’t ever matter what there is behind that funny string. What matters is that we can write something like Web.GetSomethingFrom(“some-kind-of-protocol://someone-out-there/what-we-want?color=blue&flavor=vanilla&whatnot..”) in place of the “archaic” Console.Read() or File.GetLine() or DB.Query(“SELECT…”).

Every one of these data exchanges could traverse a large number of routing points, bounce through satellites, and be converted several times to different means (electricity, light, radio waves, little messages tied to a carrier pigeon’s ankle, etc).

Dealing with sparse and remote data sources has important implications, though. The most relevant is, indeed, asynchronism. A data exchange is more like a mail exchange than a phone call. We send a request to the URI and then… wait for an answer.

Modern program flows are not like in the old days:

- Read inputs from a connected device

- Elaborate

- Write outputs to a connected device

They are more like:

- Register your interest in some subject

- Do something else

- When some event occurs, react to it (elaborate) and write the relative piece of output

We cannot any longer assume that the data we need is immediately available when we need it. Instead we need to deal with the fact that someone else decides when to send it to us. Not only that, but we must also deal with the fact that the waiting times can be several orders of magnitude longer than those required by our CPU to elaborate. In other words, we cannot afford to simply wait, we must organize our programs to use the CPU in between successive packets of data. We need to make asynchronous programs.

Asynchronous programming is nothing new, by the way. Starting from the lowest level, the CPU, most activity is based on interrupts. Hardware components, like network cards, use to interrupt the CPU when they have something to tell it. While traditionally asynchronism was under the control of hardware or the operating system in the machine, today control is lost in the internet sea - so that its management must involve the application itself, rather than the system that runs the application.

The .NET API has gone through a profound transformation over the years, making asynchronous programming progressively easier and more natural. Events were available even before .NET, and they were part of the very first C# version. In many cases, though, asynchronous programming was left to the developer code, for example running a worker thread that, in turn, cyclically polls a service checking for new data to be available.

Later we saw the callback paradigm, where asynchronous operations were based on three functions:

- Begin, to start the asynchronous operation and register a completion callback

- Callback, passed to the system in the Begin Call. The system calls it back when a relevant event occurs

- End, to be called by our code (usually at the end of the callback) to inform the system that the transaction is complete

The Task Parallel Library (TPL) was also created to ease multitasking, relieving the developer from the burden of thread management, as threads are expensive and therefore a limited resource.

The latest improvement is the async/await pattern. We are now able to write asynchronous workflows almost as a regular code blocks, while the compiler takes charge of transforming them into separate blocks with interruption and continuations, then put them into automatically created tasks, and schedule them in a coordinated way using a managed thread pool.

Asynchronous streams add a new important feature to the async/await pattern. Syntactically, the feature is quite easy to use. You simply need to:

- Supply a method returning the new interface type IAsyncEnumerable<> and containing the composite keyword yield return await in its code

- In the call site, use the new await foreach asynchronous iteration construct

The new pattern is particularly suited for scenarios where the data emitter has the characteristics of a stream. A relevant example is an Internet of Things (IoT) environment. Imagine a pool of meteorology sensors distributed across a territory, which send updates to a cloud service, either in a timely fashion, and/or when some specific condition is detected (for example, the temperature changes by at least 1 degree). This is a typical scenario for the observer/observable pattern, however, asynchronous streams help represent it in code with similar expressivity, and probably less ceremony.

Here an example, followed by some explanation and a few notes.

using System;

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Net;

using System.Text.Json;

using System.Threading;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Xunit;

namespace Cs9CheatSheet.AsyncStreams.WorldBank

{

public interface IDataSource

{

Task<string[]> DownloadIso2CodesAsync();

IEnumerable<Task<JsonElement>> DownloadCountries(string[] iso2Codes);

IAsyncEnumerable<JsonElement> DownloadCountriesStream(string[] iso2Codes);

}

abstract class DataSource : IDataSource

{

static async Task<JsonElement.ArrayEnumerator> Fetch(string url)

{

var webClient = new WebClient();

var str = await webClient.DownloadStringTaskAsync(url);

var worldBankResponse = JsonDocument.Parse(str);

var array = worldBankResponse.RootElement.EnumerateArray();

array.MoveNext(); //header

array.MoveNext(); //country(ies)

return array;

}

public async Task<string[]> DownloadIso2CodesAsync()

{

var array = await Fetch(@"http://api.worldbank.org/v2/country?format=json&per_page=100");

var countries = array.Current.EnumerateArray();

var iso2Codes = countries.Select(country => country.GetProperty("iso2Code").GetString()).ToArray();

return iso2Codes;

}

public IEnumerable<Task<JsonElement>> DownloadCountries(string[] iso2Codes)

{

for (int i = 0, n = StartFeed(iso2Codes); i < n; i++)

{

yield return DownloadCountryAsync(i, iso2Codes[i]);

}

}

public async IAsyncEnumerable<JsonElement> DownloadCountriesStream(string[] iso2Codes)

{

for (int i = 0, n = StartFeed(iso2Codes); i < n; i++)

{

yield return await DownloadCountryAsync(i, iso2Codes[i]);

}

}

protected virtual int StartFeed(string[] codes) { return codes.Length; }

protected virtual async Task<JsonElement> DownloadCountryAsync(int i, string isoCode)

{

var array = await Fetch(@$"http://api.worldbank.org/v2/country/{isoCode}?format=json");

var country = array.Current;

return country;

}

}

class CountriesDb : DataSource { }

class CountriesIoT : DataSource

{

static SemaphoreSlim[] _semaphores;

protected override async Task<JsonElement> DownloadCountryAsync(int i, string isoCode)

{

await _semaphores[i].WaitAsync();

return await base.DownloadCountryAsync(i, isoCode);

}

protected override int StartFeed(string[] codes)

{

var n = codes.Length;

async Task Feed()

{

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++)

{

await Task.Delay(1000);

_semaphores[i].Release();

}

}

_semaphores = Enumerable.Range(0, n).Select(_ => new SemaphoreSlim(0, 1)).ToArray();

Task.Run(Feed);

return n;

}

}

public abstract class Tests

{

IDataSource DataSource { get; init; }

protected Tests(IDataSource dataSource) => DataSource = dataSource;

async Task<string[]> GetRandomIsoCodes()

{

var iso2Codes = await DataSource.DownloadIso2CodesAsync();

var random = new Random();

return Enumerable.Range(0, 10).Select(i => random.Next(i * 10, i * 10 + 10)).Select(i => iso2Codes[i]).ToArray();

}

[Fact]

public async Task TestBlock()

{

var selection = await GetRandomIsoCodes();

var countries = await Task.WhenAll(DataSource.DownloadCountries(selection).ToArray());

foreach (var country in countries) AssertCountry(country);

}

[Fact]

public async Task TestStream()

{

var selection = await GetRandomIsoCodes();

var countries = DataSource.DownloadCountriesStream(selection);

await foreach (var country in countries) AssertCountry(country);

}

void AssertCountry(JsonElement country) {/*...*/}

}

public class TestsDb : Tests

{

public TestsDb() : base(new CountriesDb()) {}

}

public class TestsIoT : Tests

{

public TestsIoT() : base(new CountriesIoT()) { }

}

}

I used the WorldBank REST API for this example. It maintains a database of geographical and geopolitical information, available for free on the internet.

There is an interface called IDataSource, which abstracts our model of data emitter. On the application side, the data emitter is something that offers the following services:

- DownloadIso2CodesAsync() - Download a collection of Iso2 country codes

- DownloadCountries(string[] iso2Codes) - Download a collection of country records, with code specified in the iso2Codes input parameter

- DownloadCountriesStream(string[] iso2Codes) - Same as the previous method, but using the new Asynchronous Streams feature

Note that the two last methods, besides having different names, have exactly the same input type but different return type:

- DownloadCountries returns *IEnumerable<Task

>* - DownloadCountriesStream returns *IAsyncEnumerable

*

Both functions return lazy values, which means that the foreach loops they implement won’t be executed when the functions return. And they will be executed only when the last lines of TestBlock() and TestStream() are reached in the Tests class. These two test methods have:

-

A first common part, where they download a set of ISO codes (100 in the example) and select ten of them randomly

-

A second part where they retrieve detailed information about the selected countries, but in different ways

Let’s now concentrate on the last two lines, where the key differences are manifested:

-

TestBlock calls DownloadCountries and receives a collection of Tasks. It then executes them in parallel using the Task.WhenAll TPL API. When all the tasks complete, the collection of results is returned as an array, referenced by the countries symbol. Finally, the last line runs an iteration synchronously on the hydrated array and does application-specific work.

-

TestStream calls DownloadCountriesStream and receives an IAsyncEnumerable, referenced by the countries symbol. This is the first difference. The symbol countries does not hold a hydrated array of countries like with TestBlock, but a promise. When the last line is reached, nothing has been materialized from the data sources yet, while with TestBlock the materialization is already complete. Finally, TestStream executes an asynchronous iteration calling the new await foreach. This is the point where the internet is finally hit and the remote data is retrieved

At this point, it’s worthwhile to highlight a qualifying point. In the TestBlock case, we have the opportunity to leverage the TPL, while in the TestStream case we don’t. This has two potential consequences:

- Performance: If the backend has already available all the countries in our selection at the time the requests come, TestBlock will get all the cities in roughly the same time required to retrieve only one of them. TestStream, on the other hand, is constrained to a sequential workflow, so the time will necessarily be the sum of the times for each of the cities in the selection

- Memory: The block version will allocate memory for all the cities, while the stream version only needs to allocate memory for one.

Therefore, if the backend has all the data, choosing between block and stream is a tradeoff between memory resources and performance. Usually, in situations like this, the best solution is the parallel one with pagination.

However, if the backend does not have all the data, like the meteorology sensors I mentioned above, the performance advantage of parallel execution is nil, since even if the tasks are running in parallel, only one of them will complete just after the launch. The remaining tasks will need to wait until new data is available. In this case, the stream solution is definitely superior, as it will give the results in the same time, but with less memory use and with only one pending task during the data retrieval period.

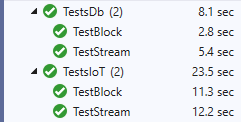

In the previous example, this is demonstrated by creating two implementations of IDataSource: CountriesDb and CountriesIoT. CountriesDb behaves like a database. That is, it simulates a data source that responds immediately upon request. CountriesIoT, instead, simulates an IoT device, with data items available one by one at one-second time distance. (The trigger is the task started in StartFeed where a pool of semaphores are released over time, while the overridden DownloadCountryAsync awaits one of the semaphores before doing active work). Running the tests produces the following results:

With a db-like data source, the block workflow executes in half of the time taken by the stream workflow. With the IoT-like data source, on the other hand, times are comparable.

Recap

In this article, you have explored some of the important improvements introduced into C# versions 8 and 9. What you learned:

- Immutability: Init-Only Properties, Records, Positional Records, Static Local Functions

- Default Interface Methods: Non-Breaking Interface Augmentation

- Pattern Matching: Switch Expression, Type Check Pattern, Property Pattern

- Compactness: Indices and Ranges, Null Coalescing, Target Type Inference

- Type Extensibility: Covariant Returns, Enumerability By Extensions

- Asynchronous Streams

Learn More About .NET, C# 8 and C# 9

If you are interested in learning more about C# 8 and C# 9 check out these other great articles:

- Okta ASP.NET Core MVC Quickstart

- Secure Your ASP.NET Core App with OAuth 2.0

- Build Single Sign-on for Your ASP.NET MVC App

- Policy-Based Authorization in ASP.NET Core

- Store ASP.NET Secrets Securely with Azure KeyVault

- User Authorization in ASP.NET Core with Okta

- What’s new in C# 8.0

- What’s new in C# 9.0

- Welcome to C# 9.0

If you like this topic, be sure to follow us on Twitter, subscribe to our YouTube Channel, and follow us on Twitch.

Okta Developer Blog Comment Policy

We welcome relevant and respectful comments. Off-topic comments may be removed.