SQL Injection in PHP: Practices to Avoid

SQL injections are one of the most common vulnerabilities found in web applications. Today, I’m going to explain what a SQL injection attack is and take a look at an example of a simple vulnerable PHP application accessing a SQLite or MySQL database. After that, we’ll look at several methods to prevent this attack, fixing the problem.

Prerequisites

Make sure you have the following software installed and enabled on your system:

Set up and start the exploitable PHP application

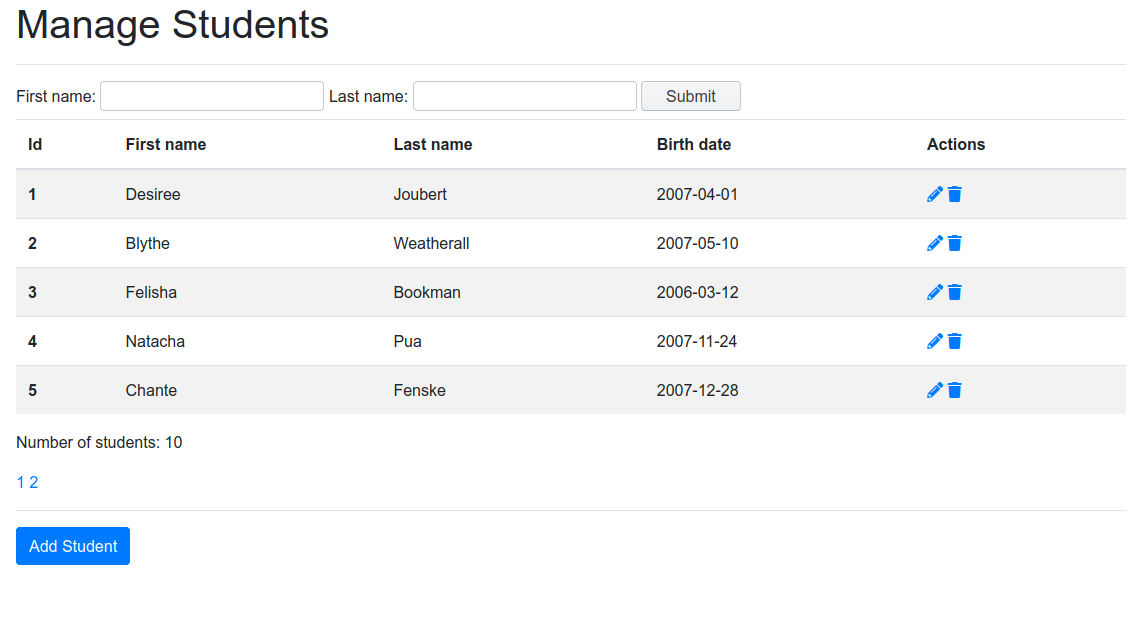

First, we are going to set up our vulnerable example application. It’s a really small self-contained PHP web application that manages a list of students from a SQLite database (also included in the app) accessed through the PDO PHP extension.

Let’s download the source code from GitHub.

git clone https://github.com/oktadeveloper/sql-injection-in-php.git sql-injection-in-php

cd sql-injection-in-php

composer install

After this, you can simply execute the PHP built-in server in the port 8080 (you can choose another port if you wish):

php -S localhost:8080

PHP 7.2.29-1+ubuntu19.10.1+deb.sury.org+1 Development Server started

Listening on http://localhost:8080

Document root is /home/okta/sql-injection-in-php

Press Ctrl-C to quit.

Now, visit the vulnerable app from your browser by navigating to http://localhost:8080.

Essentially, the application allows the user to search students by their first or last names, to add new students, and to edit or delete existing ones.

The application is quite basic and designed to easily show the existing SQL injection vulnerabilities just by using the browser. For example, it uses the HTTP method GET for all transactions (although usually forms would be sent using methods POST or PUT).

Also, the database also includes some clear-text passwords. This is for the sake of clarity in this tutorial—I honestly hope you don’t ever design a database or an app this way.

What is a SQL Injection?

A SQL injection is a type of vulnerability that gives users access to the database associated with an application, allowing them to execute SQL queries.

Using this access, an attacker can retrieve information from the database in an unauthorized way (especially from those tables that aren’t typically accessible by users). Also, it is possible to insert, update, or delete records.

Exploit a Simple SQL Injection Vulnerability

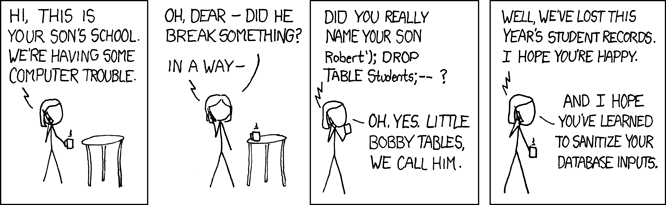

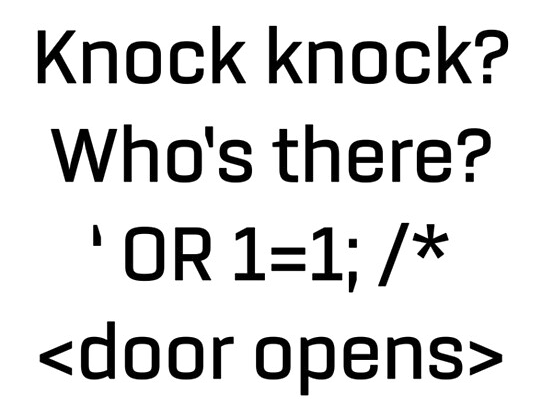

So, how can we exploit our vulnerable application? A very good example is this classic XKCD comic strip:

Fundamentally: applications vulnerable to SQL Injection attacks don’t properly sanitize their inputs, so an attacker can introduce new conditions and/or queries.

Before using SQL injection to drop the students table, let’s play with it a bit.

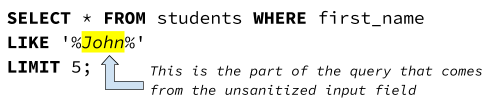

In a vulnerable application, SQL queries are typically created by concatenating strings with the different parts of the query. The data from an unsanitized input would be one of these parts.

In SQL, string parameters are wrapped between quote symbols. Usually, they use single-quotes ', though some database servers also allow using double-quotes " to wrap strings. These quote symbols separate string parameters in the SQL query from all the other components of the query.

We are going to try escaping from the SQL query field parameter—in which the application used the input—so it becomes something else.

So, if we are trying to escape from a string in SQL, we will need to use the same wrapping character that was used to start the string. As we said, this is typically the single-quote ', although some database engines also support the double-quote ". After this character, we need to add contents so the SQL query is still valid. And, finally, we need to mark the end of the SQL command (with the semicolon character ;). We also need the server to ignore the remaining characters added by the original software, so we’ll typically use the strings --, # or /*, depending on the engine running the database server. In our case (SQLite), we’ll use --.

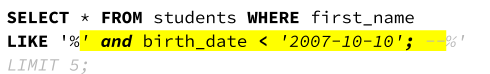

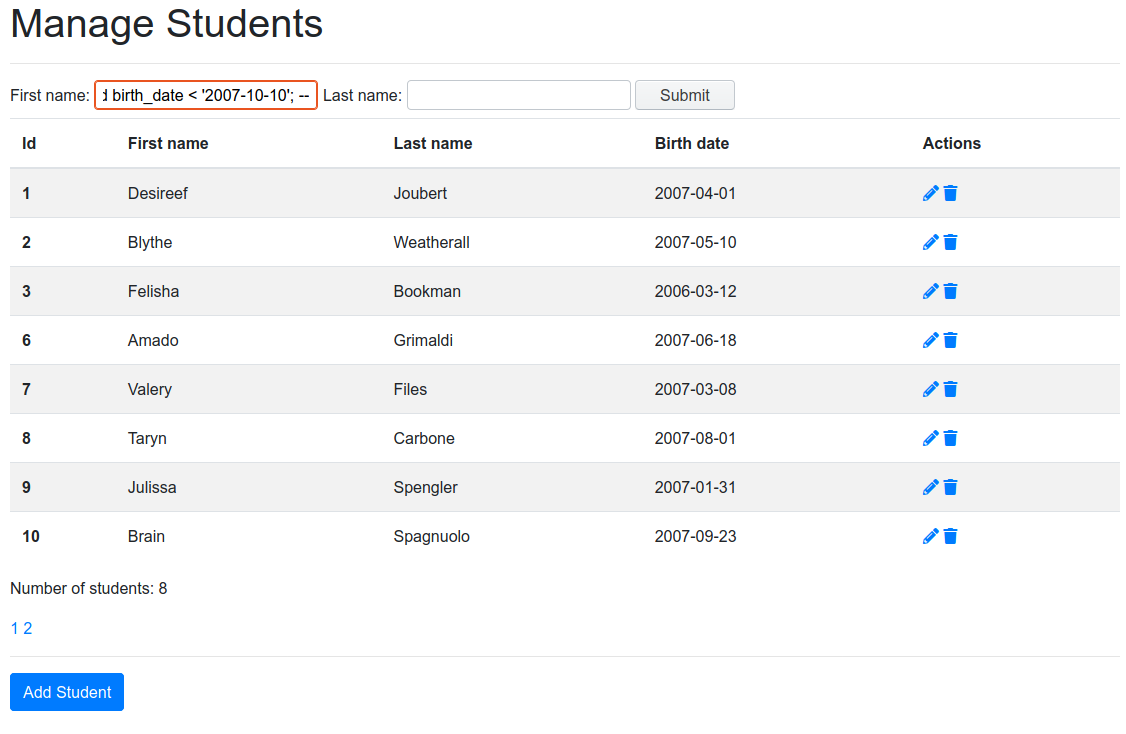

So, let’s try searching for students including the following first name:

' and birth_date < '2007-10-10'; --.

The application will build this SQL query (with the highlighted part coming directly from the input field):

By escaping from the place where the input string was originally intended, we get these results.

We have filtered the list of students, only looking at the ones with a birth date from before October, 10th, 2007. Additionally, the limit that shows only 5 students per screen has been disabled. Essentially, we have taken control of the returned output.

As we can see in the code of includes/search.php (lines 25-45), the SQL query is generated without properly escaping any of the inputs.

$count_query = 'SELECT COUNT(*) as num_rows from students where hidden=0 ';

$query = 'SELECT id, first_name, last_name, birth_date from students where hidden=0 ';

$filters = '';

if ( ! empty( $first_name ) || ! empty( $last_name ) ) {

if ( isset( $_GET['first_name'] ) && ! empty( $_GET['first_name'] ) ) {

$filters .= "AND first_name LIKE '%{$_GET['first_name']}%' ";

}

if ( isset( $_GET['last_name'] ) && ! empty( $_GET['last_name'] ) ) {

$filters .= "AND last_name LIKE '%{$_GET['last_name']}%' ";

}

}

$page = $_GET['page'] ?? 1;

$query .= $filters . ' LIMIT 5 OFFSET ' . ( $page - 1 ) * 5;

$result = $pdo->query( $query );

The filters first_name and last_name are taken as they come, without taking any action to filter the introduction of quotes or other escaping characters to prevent the user from adding their own commands.

PDO, the database library that we are using to communicate with the SQLite database, doesn’t allow introducing multiple commands in a single database query to get a result (the second query will be ignored). But we can still exploit this query to get extra information about the database.

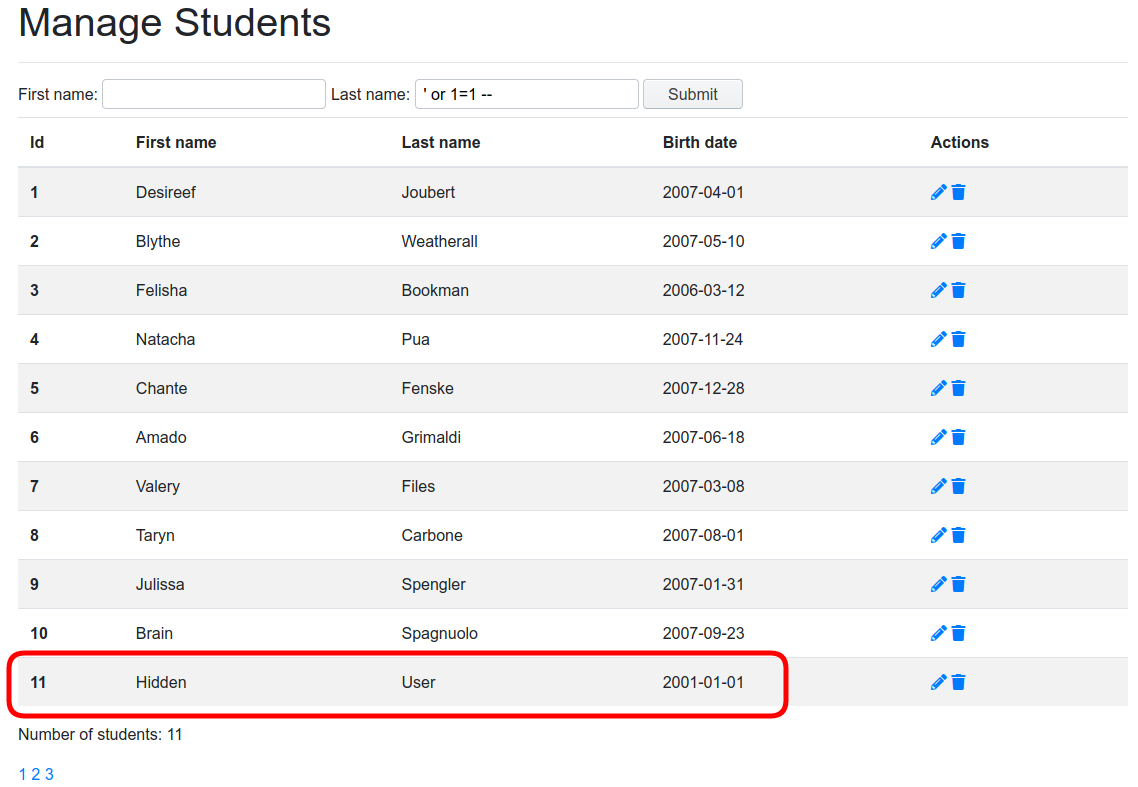

For example, looking at line 25, we can see that we only see those students with hidden=0. So, let’s try viewing hidden users. We can search for students with the following last name: ' or 1=1 ;--

And, voilà: we can see the full list of all students, including those that were previously hidden (only one, in our example database).

Types of SQL Injection

We can classify SQL Injection vulnerabilities into several categories. Let’s examine them.

In-band SQL Injection attacks

These are the most common category and the easiest to exploit. In these attacks, the attacker uses the same communication channel to launch the SQL Injection and to collect the corresponding results. These are the same exploits we’ve been using in our app; we manipulate the inputs of the web application to execute our own queries and retrieve the results in the same web app.

We can talk about different sub-categories for in-band SQL injection attacks:

Boolean-based SQL Injection

In this subcategory, the attacker modifies a boolean condition in a SELECT, UPDATE, or DELETE clause in order to retrieve extra information or to modify or delete rows that never would have had to be modified or deleted in normal conditions.

The previously shown attacks affecting the students table SELECT clause would fall into this subcategory.

Error-based SQL Injection

This technique seeks to retrieve information about the structure of the database using error messages returned by the database server. By using this technique, an attacker can retrieve valuable information about the database, such as if a given table exists in the database or not.

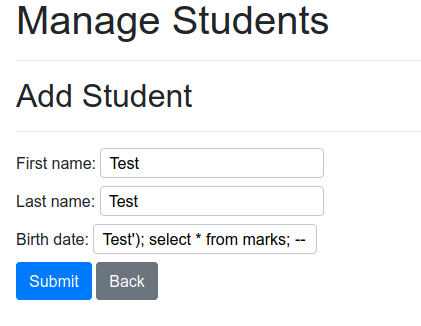

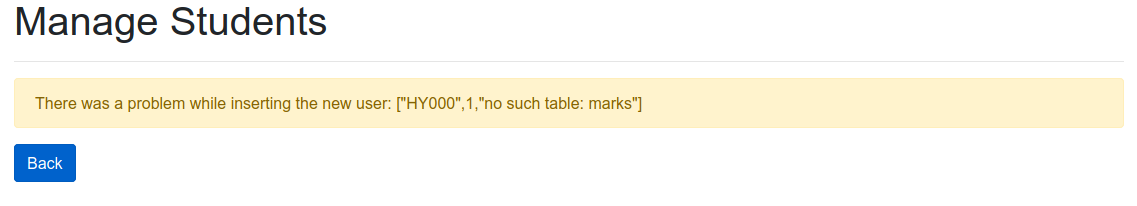

For example, we could try exploiting this kind of attack via the new student form at http://localhost:8080/manageStudent.php?action=insert. We can introduce a student injecting SQL into the last field. First, we can try to find out if the tables ‘marks’ or ‘teachers’ exist in the database.

To find out if the marks table exists, simply enter Test'); select * from marks; -- in the Birth Date field.

And we’ll get the following result:

So we know that the marks table doesn’t exist.

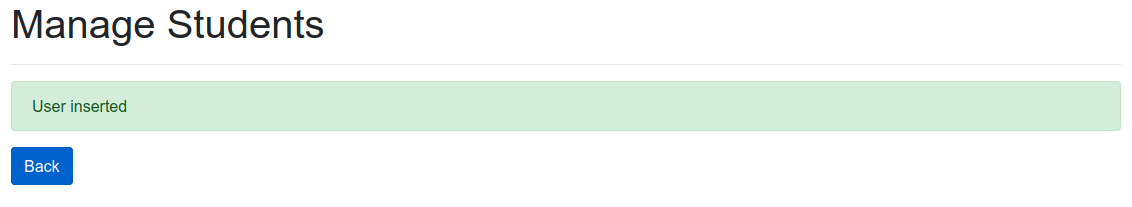

Let’s try again with the teachers table. We’ll now add another student with Test'); select * from teachers; -- as the birth date.

In this case, we don’t obtain any error, so we can assume that there’s a table named teachers.

Using this method, along with a lot of patience (and/or some automated scripts) we could determine the whole structure of the database, finding information about all of the tables and the existing columns.

That’s why it is crucial to never show database error information to the end user. These messages are very useful while developing or debugging the application, but they should be completely disabled or sent to an error log once the app reaches production.

Concatenated-commands SQL Injection

Using the insert interface, we are able to inject SQL code and ee any resulting error message. We can use this interface to obtain information, but we also have a powerful exploiting point that allows us to introduce any valid command into the database just by concatenating commands.

For example, an attacker can create tables, insert records, update records, delete tables—all dependent on their will.

So, using this, we could create a student with a birth date 2001-01-01'); DELETE from table students; and the table students would be immediately emptied.

This is exactly what the owner of this car tried. Not sure if successfully.

Union-based SQL Injection

Previously, we exploited the student search interface to retrieve hidden records, or to change the way in which the information is returned by the database.

But we can exploit this same interface by using the UNION SQL command to retrieve data from other existing tables in the database. We are limited to select the same number and type of columns we already had in the original SELECT, but we always can use tricks to circumvent this.

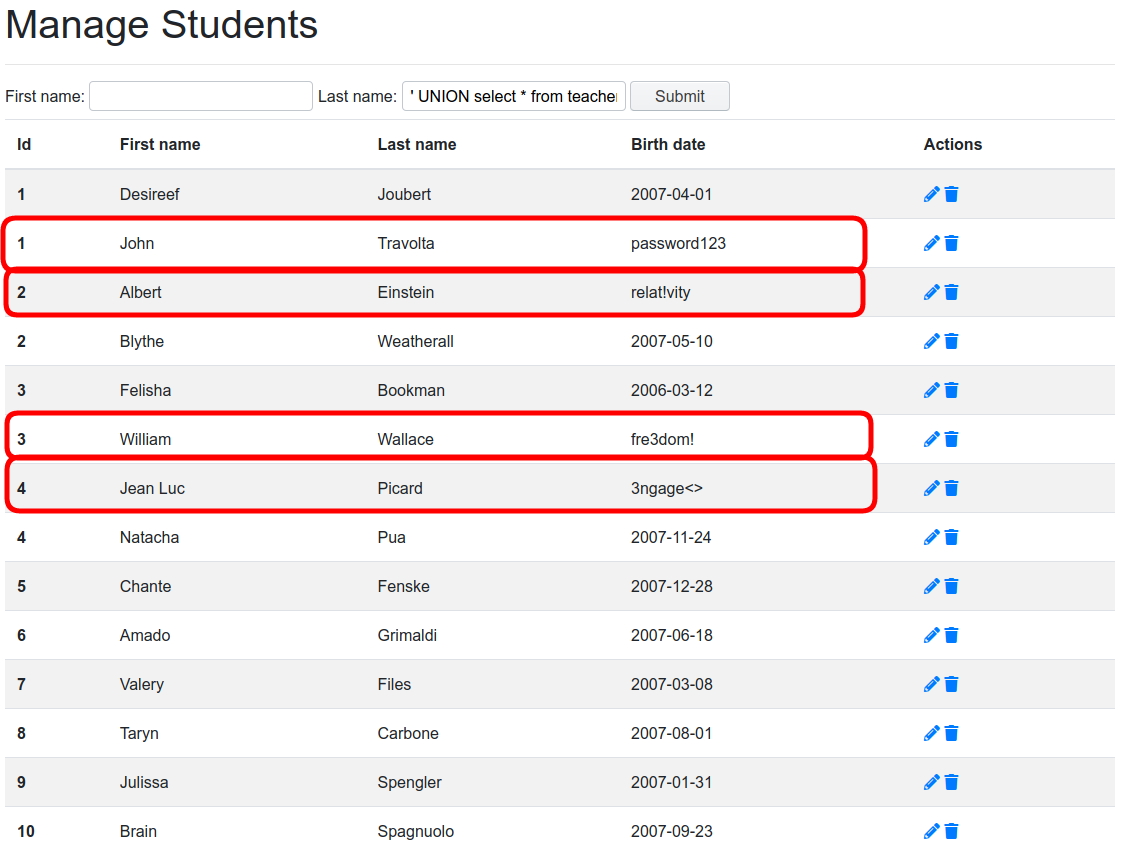

For example, as we already know that the teachers table exists, we could try checking its contents. We could search for students with last name ' UNION select * from teachers ; --

This does, indeed, yield results: that table has the same number of columns as the original select:

It seems that the teachers table included a field with a clear password! This was a really successful attack. Now, any student using this hypothetical app could impersonate a teacher and modify his/her qualifications!

Inferential SQL Injection attacks

In Inferential SQL Injection attacks, no return data is transferred through the channel used to send the manipulated input—including the attack. But an attacker is able to reconstruct the database structure by sending payloads and checking the web application’s response and/or behavior.

We have two types of inferential attacks: boolean-based and time-based.

Blind boolean-based SQL Injection Attacks

This kind of attack relies on sending a SQL query that will force the application to return a different result depending on if a given condition included in the query is true or false.

For example, if the database error-logging is disabled (and the error-based SQL Injection attack is no longer possible) we can use this method to scan tables and or columns in the database.

We could check if the classes table exists by searching students with the following last name:

' AND CASE WHEN (select count(*) from classes) >= 0 THEN true ELSE false END ; --

We wouldn’t obtain any result, so we could infer that the classes table does not exist.

But, if we repeat the process for the qualifications table, checking for students with the last name ' AND CASE WHEN (select count(*) from qualifications) >= 0 THEN true ELSE false END ;--, the app will return all the students from the database, so we know now that this table does exist.

Again, by using this method over and over, probably using an automated script, we’ll be able to determine the whole structure of the database, finding information about all the tables and the existing columns.

Blind Time-based SQL Injection Attacks

This kind of attack tries to infer information about the database or the database server by examining the time the database spends answering a given query.

SQLite is not vulnerable to this kind of attack, as it doesn’t include any function that forces a delay in the executed query, nor does it include functions that take a lot of time to be executed.

Other databases such as MySQL allow this kind of attack—thanks to the existence of functions like SLEEP() and BENCHMARK(). This attack can tell us if the database server running a given application is MySQL. For example, if in the MySQL-based version of the app we seek users with the following last name ' and id=sleep(5) ; --, the query will sleep for 5 seconds or more, confirming that the app is running against a MySQL server.

Additionally, the attacker might be interested in verifying a few assumptions. This can be easily done by integrating the time delay inside a conditional statement. For example, we could check the running MySQL/MariaDB database version by searching for students with the following last name: ' and id=if(LEFT(VERSION(),2)='10',SLEEP(2),1) ; -- .

If running MariaDB 10, the query would take 2 seconds or more to complete.

These time-based attacks could also be used to cause a denial of service. By forcing the execution of several long queries simultaneously, an attacker could deplete the number of database listeners, making the app inaccessible for others.

Out-of-band SQL Injection attacks

These kinds of attacks occur when the result of the attack is not related to the channel used to trigger it but is received by other media instead. They are especially useful if the time-based techniques are not reliable because the time spent by the server when executing queries fluctuates too much.

They depend on features that must be enabled on the database server used by the web application; for example, the ability to make DNS or HTTP requests to deliver data to the attacker. These features are available in databases like Microsoft SQL Server (via the xp_dirtree command) or Oracle (via the UTL_HTTP package).

Preventing SQL Injection attacks in PHP

So, which measures should you take to prevent SQL injection attacks?

It’s actually quite easy. First, you must sanitize your inputs. Always. No excuses. Don’t ever trust incoming data. The optimal and safest way to sanitize inputs when building SQL queries is by using prepared statements.

And, as an additional note, don’t rely on client-side input sanitation. An attacker could launch SQL Injection attacks emulating the calls from a browser, using unsanitized data.

How to Use Prepared Statements

As stated previously, the best way to sanitize inputs when building SQL queries is by using prepared statements.

So, the unsafe code from includes/delete.php:

$id = $_GET['id'];

$delete_query = 'DELETE FROM students where id = ' . $id;

$result = $pdo->exec( $delete_query );

where the $id parameter isn’t sanitized when building the executed SQL query will become: in includes/deleteSafe.php:

$id = $_GET['id'];

$delete_query = 'DELETE FROM students where id = :id';

$prepared_statement = $pdo->prepare( $delete_query );

$prepared_statement->bindParam( 'id', $id );

$prepared_statement->execute();

$result = $prepared_statement->rowCount();

The PDO library and/or its dependencies will take care of applying the corresponding escaping to the provided parameters when binding parameters.

A similar method is used in includes/searchSafe.php:

$query = 'SELECT id, first_name, last_name, birth_date from students where hidden=0 ';

$filters = '';

$parameters = [];

if ( ! empty( $first_name ) || ! empty( $last_name ) ) {

if ( isset( $_GET['first_name'] ) && ! empty( $_GET['first_name'] ) ) {

$filters .= "AND first_name LIKE :first_name ";

$parameters['first_name'] = $_GET['first_name'];

}

if ( isset( $_GET['last_name'] ) && ! empty( $_GET['last_name'] ) ) {

$filters .= "AND last_name LIKE :last_name ";

$parameters['first_name'] = $_GET['last_name'];

}

}

$page = $_GET['page'] ?? 1;

$query .= $filters . ' LIMIT 5 OFFSET :page';

$parameters['page'] = ( $page - 1 ) * 5;

$prepared_query = $pdo->prepare( $query );

$prepared_query->execute( $parameters );

$result = $prepared_query->fetchAll();

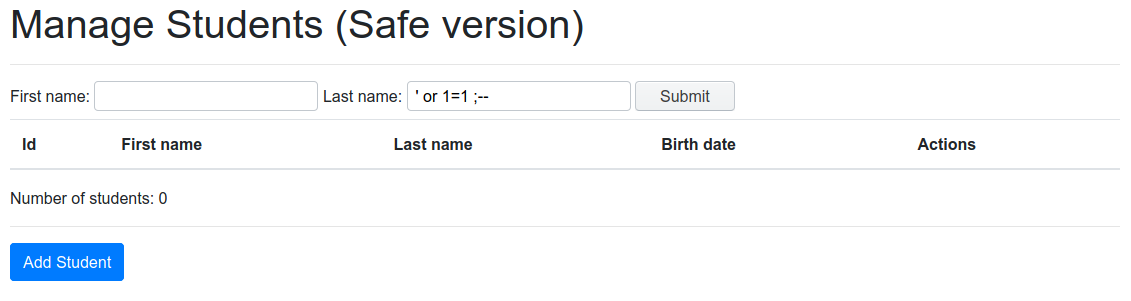

The safe version of the app, available at http://localhost:8080/manageStudentSafe.php, filters and sanitizes all the inputs used to build SQL queries, preventing SQL injection attacks.

How not to use prepared statements

It’s very important that you never build prepared statements with parameters by simply concatenating them to the prepared statement, as in:

$a->prepare("UPDATE `users` SET user='$var'");

This would still make the prepared statement vulnerable to SQL Injection attacks. Always keep in mind that the only feature in prepared statements that prevents these attacks is the parameter binding step.

What to do if you don’t use PDO to access the database?

This example application uses the PDO library to access SQLite and MySQL databases. But this is not the case for all applications.

In those cases, you must find the way in which your database abstraction library implements prepared statements with parameter binding.

For example, when using MySQLi library, the functions would be:

$sql = "SELECT * FROM students WHERE first_name=?"; // SQL with parameters

$stmt = $conn->prepare($sql);

$stmt->bind_param("s", $_GET['first_name']);

$stmt->execute();

$result = $stmt->get_result(); // get the mysqli result

$user = $result->fetch_assoc(); // fetch data

When using WordPress:

$prepared_query = $wpdb->prepare( "SELECT * FROM students WHERE `first_name` = %s", $_GET['first_name']);

$results = $wpdb->get_results( $prepared_query );

When using PostgreSQL:

$result = pg_prepare($dbconn, "my_query", 'SELECT * FROM students WHERE first_name = $1');

$result = pg_execute($dbconn, "my_query", array($_GET['first_name']));

So, basically, every method to access the database has its own way of implementing this feature. Just look for it and use it!

Using stored procedures

Using stored procedures in the database is also often recommended in order to prevent SQL Injection attacks.

Like prepared statements, they can be a good solution. Let’s take a look at an example for MySQL.

To create a new stored procedure, use the CREATE PROCEDURE statement with the following syntax.

DELIMITER //

CREATE PROCEDURE procedure_name(parameter_list)

BEGIN

statements;

END //

DELIMITER ;

We use the DELIMITER keyword to temporarily change the SQL-sentence delimiter, so the stored procedure can include semi-colon characters.

If the statements just include a single SQL query, the procedure will return the output of the query.

For example, let’s build a procedure that retrieves the list of students with a given first name:

DELIMITER //

CREATE PROCEDURE secure_student_search_first_name (IN fname VARCHAR(1000))

BEGIN

SELECT * FROM students where first_name=fname;

END //

DELIMITER ;

We can use output parameters as well:

DELIMITER //

CREATE PROCEDURE secure_student_count_first_name (

IN fname VARCHAR(1000),

OUT total INT

)

BEGIN

SELECT COUNT(id) INTO total

FROM students WHERE first_name = fname ;

END//

DELIMITER ;

To retrieve the number of students with a given first name we would execute:

CALL secure_student_count_first_name('John',@total);

SELECT @total;

Stored procedures will automatically bind the procedure parameters into the SQL queries inside of the BEGIN-END block, avoiding SQL-Injection attacks.

But, if used incorrectly, stored procedures might not be a solution at all. For example:

DELIMITER //

CREATE PROCEDURE insecure_student_search_first_name (IN first_name VARCHAR(1000))

BEGIN

SET @sql = CONCAT('SELECT * FROM students where first_name=\'', first_name, '\' ');

PREPARE stmt FROM @sql;

EXECUTE stmt;

DEALLOCATE PREPARE stmt;

END //

DELIMITER ;

This last procedure is still vulnerable against an SQL Injection attack, as we are building the executed SQL query as a string by concatenating several strings instead of using the automatic binding support. For example, when called this way:

call insecure_student_search_first_name ('\' OR 1=1 OR \'\'=\'');

It will return the whole list of students.

So it all depends on if you design the stored procedures so they use prepared statements. If you do it wrong, you could still be vulnerable to an SQL Injection attack.

Learn More About Web Security and PHP

SQL injection vulnerabilities are ubiquitous in web applications. But, as you’ve seen, just by applying some basic techniques you can easily prevent your applications from being exploited. Basically, always be sure to sanitize user input carefully, using prepared statements or stored procedures.

There are several free vulnerability-scanner tools that you could use to get sure that your web applications aren’t vulnerable.

This post showed you the importance of protecting your application against SQL Injection vulnerabilities. Want more security-related content for developers? Check out some of our other posts:

- Add Authentication to your PHP App in 5 Minutes

- A Developer Guide to Reporting Vulnerabilities

- Securing REST APIs

- Why JWTs Suck as Session Tokens

- Use PKCE with OAuth 2.0 and Spring Boot for Better Security

If you have questions, please leave a comment below. If you liked this tutorial, follow @oktadev on Twitter, follow us on LinkedIn, or subscribe to our YouTube channel.

PS: We’ve just recently launched a new security site where we’re publishing in-depth security articles and guides. If you’re interested in infosec, please check it out. =)

Okta Developer Blog Comment Policy

We welcome relevant and respectful comments. Off-topic comments may be removed.