A History of the Mobile SSO (Single Sign-On) Experience in iOS

On an iPhone, when we log in to an app, we click a login button, and a website pops up to verify our credentials. Once verified, the website then redirects back to the app, and you are logged in. This familiar Single Sign-On (SSO) pattern is frequently referred to as the redirect flow for authentication. The use of a web browser for auth in this example is considered a “Best Current Practice” for security and usability reasons.

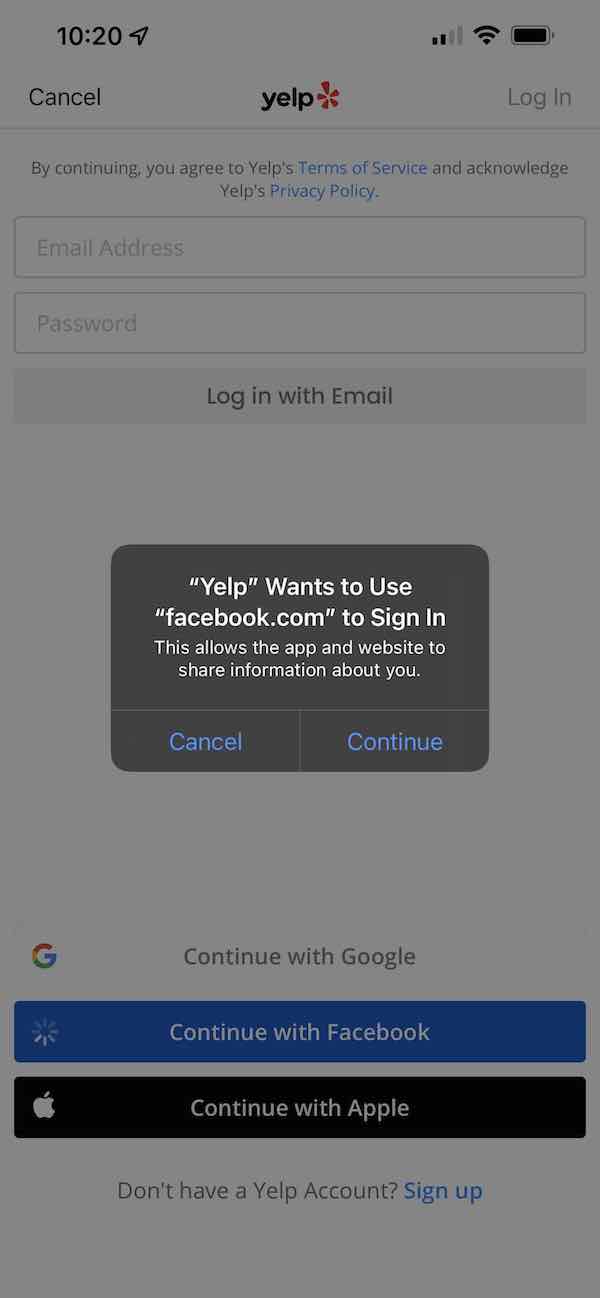

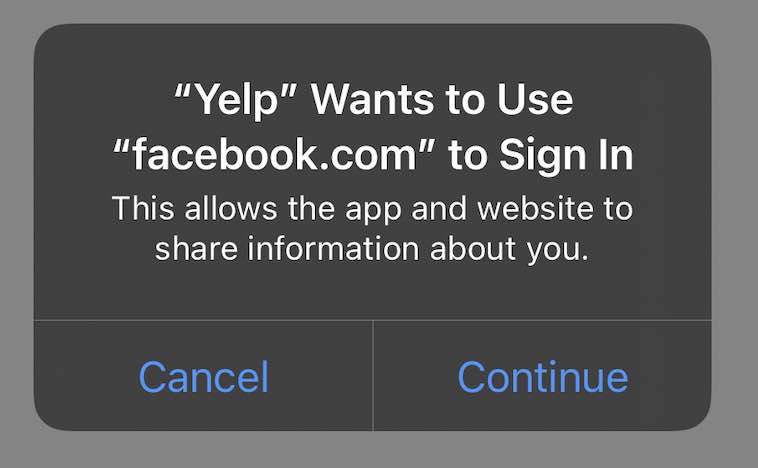

However, in 2017, a new prompt appeared in the login flow, before you were taken to the website. The following screenshot came from an iOS app preparing to log you in with Facebook. The interface prompt informs you that a specific app, the Yelp app in this example, wants to use a specific website to sign you in, and it warns you about information sharing.

The main reason this prompt was added was to provide users more context about why a third-party website is about to appear, as well as surface the website domain to the user in a system-level prompt that can’t be faked by the app. Without the prompt, the user would immediately be taken to the Facebook login screen. A malicious app might open a fake website that mimics the Facebook login screen and try to steal the user’s credentials. With this prompt in place, the user will first see the domain the app is launching, in this case “facebook.com”, and would provide the user with an opportunity to recognize a phishing attempt before seeing the login page.

In this article, I’ll go into more detail on why this prompt is shown and a bit of the history of why this prompt ended up being added in iOS.

A brief history of iOS evolution

The browser options available for authentication on an iOS device have changed significantly over the years, as Apple continues to add capabilities to enhance user privacy. To understand the behavior of the browser options provided on iOS, some historical context is helpful.

Authentication prior to iOS 9

Before the release of iOS 9 in 2015, there were only two ways to authenticate through a web browser, and neither one was optimal.

-

UIWebView. This approach shows web content in aUIView. The mobile app can intercept interactions with theUIView, hence it is not secure. -

Redirect to an external browser. The mobile app can open a webpage in a separate browser app, and the browser app can redirect back to the mobile app after authentication. However, app switching is not a good experience for mobile users. In addition, the redirect back can fail if another app has registered the same custom URL scheme first.

Authentication in iOS 9 (2015)

In 2015, Apple introduced SFSafariViewController, which displays an embedded Safari browser in the app. As an in-app browser tab, this interface lets the user stay in the app. Once the user interaction with the website is no longer needed, the browser tab can be closed and dismissed.

This solution was groundbreaking, because it is secure (the native app can neither peek into the embedded browser, nor alter its state) and it provides a better user experience by avoiding app switching.

SFSafariViewController shares cookies with the standalone Safari browser. This gives developers a way to implementSSO (Single Sign-On) with shared cookies.

iOS 11 changes (2017)

Apple changed SFSafariViewController behavior to address privacy concerns with the release of iOS 11 in 2017. SFSafariViewController no longer shares cookies with the standalone Safari browser. Thus, a website can no longer determine that the user on SFSafariViewController is the same user on Safari, even though the view controller and the browser are open on the same device.

Apple understood that the SFSafariViewController behavior change would break SSO, since single sign-on relies on the ability to share cookies. Instead, Apple had to introduce SFAuthenticationSession as a workaround, where SFAuthenticationSession would share a persistent cookie with Safari.

Iterative changes in iOS 12 (2018)

In 2018, Apple deprecated SFAuthenticationSession, but introduced ASWebAuthenticationSession as a revised solution.

Both SFAuthenticationSession and ASWebAuthenticationSession are designed specifically for OAuth 2.0 authentication, not for showing general web content. To avoid abuse, when SFAuthenticationSession or ASWebAuthenticationSession are used, Apple always displays the prompt we saw earlier. The prompt is designed explicitly for user sign-in, and indicates that cookies are shared.

Apple does not know whether an ASWebAuthenticationSession is invoked for sign in, sign out, or general web browsing. This is why the prompt text is generic. It only states that your app is trying to Sign In, regardless of the actual use case.

iOS 13 changes (2019)

In 2019, Apple introduced prefersEphemeralWebBrowserSession as an option for ASWebAuthenticationSession. If this option is set to true, ASWebAuthenticationSession does not show the prompt above, and as a consequence, it does not share cookies with Safari. This gives developers a choice. Either they gain a better user experience with no confusing prompt and no SSO, or they get SSO, along with the annoying prompt.

SFAuthenticationSession or ASWebAuthenticationSession behavior

The various browser options offer differing levels of cookie sharing in order to limit websites’ ability to track a user.

The cookie-sharing behavior is not well documented in Apple’s documentation. The SFSafariViewController doc mentions that, “In iOS 9 and 10, it shares cookies and other website data with Safari … If you would like to share data between your app and Safari in iOS 11 and later, … use ASWebAuthenticationSession instead.”

A few third-party websites extend Apple’s documentation to highlight that persistent cookies are shared between an embedded browser and Safari. Unfortunately, it is rarely known that session cookies can also be shared between different embedded browsers. If your application just needs SSO between your mobile apps, you do not have to use a persistent cookie; a session cookie is sufficient.

The following table summarizes the complete sharing behavior in iOS 11 or later. I’ve omitted SFAuthenticationSession for brevity because it is deprecated, but it behaves the same as ASWebAuthenticationSession. I’ve also omitted the prefersEphemeralWebBrowserSession option for ASWebAuthenticationSession because when it is set, cookies are not shared at all.

I also use SVC as shorthand for SFSafariViewController and WAS as shorthand for ASWebAuthenticationSession.

| APP1 + SVC | App1 + WAS | App2 + SVC | App2 + WAS | Safari | Other browsers (ex.: Chrome) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session cookie | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Persistent cookie | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

In the following iOS cookie behavior demo video, you can see how the session cookie and the persistent cookie are shared. The session cookie sharing behavior is not intuitive. Even when App1 is closed (which should clear all session cookies), opening App2 would make it possible to see App1’s session cookie.

It is worth noting that in iOS 14 and later you can specify another browser, such as Chrome, as the default. This does not affect the sharing behavior. SFSafariViewController and ASWebAuthenticationSession always use Safari under the hood, so they will never share cookies with browsers other than Safari, even if they are set as the default. The term system browser, often used in online articles, is synonymous with Safari.

Summary

Understanding iOS and Android platform-level constraints is a prerequisite for developing great mobile experiences. I hope this article will help you understand the browser options available on iOS and their cookie sharing behaviors.

Feel free to add your questions and suggestions about this solution or future topics in the comments below.

If you enjoyed reading this article, you can keep up with our content for developers by following us on Twitter and subscribing to our YouTube channel.

Okta Developer Blog Comment Policy

We welcome relevant and respectful comments. Off-topic comments may be removed.